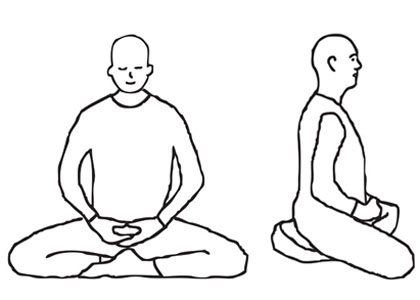

We start with finding a comfortable meditative posture. We’ll close our eyes and focus our attention on the breath for some time to become calm and concentrated. [60sec.]

In the beginning of this practice some people might have difficulties in developing the feeling of loving kindness, to experience the actual emotion of loving kindness. As a preliminary exercise try to imagine a young pet, a little dog or cat as it is playing in its clumsy ways or try to imagine a baby or little child as it is smiling at you. Nobody would do any harm to these little beings, there is only care and well-wishing. The emotion that normally now arises in your mind is the feeling of loving kindness we are looking for.

Now imagine the kindly shining sun that radiates its energy, both rays of light and warmth towards all things, living or nonliving, to all human beings of all races and religions in all parts of the world without preference or prejudice. [30 to 60sec.]

Now imagine yourself as this lovely shining sun with all loving kindness as its energy and start radiating the loving kindness as the sun does with its rays of light and warmth. [30 to 60sec.]

To yourself (not easy for some)

Now bring up an image of yourself that you can recall best.

Try to see yourself smiling at you. [30 to 60 sec.]

Now slowly repeat these words in your mind:

- May I be happy and well.

- May I be far away from troubles and dangers.

- May I live happily in peace.

Before you repeat the loving kindness phrases (May I be ...) you can reflect on your life in order for loving kindness to arise more easily: [...]

Some common phrases used in loving kindness meditation: Choose whichever you find appropriate, invent your own phrases. Three or four phrases are enough, no need to use all of them any time.

- May ... be happy and well. ( ... = I or you or, he, she, they, we)

- May ... be safe and warm.

- May ... be far away from troubles and dangers.

- May ... not be parted from the good fortune ... have attained.

- May ... live (exist) happily in peace.

- May ... have mental happiness.

- May ... have bodily well-being.

- May ... be able to let go of anger, fear, worry and ignorance.

- May ... be open to life.

- May ... be free from all suffering.

To a respected person

Now bring up an image of one of your teachers or of a person you’ve learned from or of somebody who is or was benevolent to you. [30 to 60 sec.]

To our parents (can be difficult for some)

To somebody who is dear to us

To people who gave us some difficulties (best not to start with your greatest enemy)

Reflections:

- This person is struggling for life as I do. (Use his/her name instead of "person").

- This person makes mistakes as I do.

- He/she has to deal with his/her anger, fear uncertainties, wrong views as I have to.

- By following his/her way of life as I’m following my way of life, he/she has given me another perspective of life to learn.

- He/she has shown me some of my weak points so that I can improve myself.

I will forgive him/her as other people have forgiven me and radiate my loving kindness to him/her.

To all beings

Bring your attention back to yourself. Feel your heart filled with loving kindness, compassion and sympathetic joy. [30 to 60 sec.]

Now extend your loving kindness to all human beings of all races and religions without prejudice.

Extend your loving kindness further to all animals, plants,...

Then slowly repeat these words in your mind:

Other possible receivers of our loving kindness may be people with difficulties and/or suffering like victims of natural catastrophes or wars, people in jail or with diseases...

Return to the Meditation top level page

We want to be aware of the sensations the breath causes along its way in our body. At first we let the breathing go comfortably and naturally without influencing it. When we inhale the air enters the nose. We can be aware of this at some point at the inner skin of the nose, the nostrils or the upper lip. If you have difficulties to find the point of touch, you may breathe forcefully for a couple of breaths. Then the air travels along the upper palate and the throat into our lungs (which is difficult to be aware of) and we will notice that our chest widens and the belly rises. Then there is a gap between in- and exhalation and when we start exhaling, we are aware of the abdomen sinking back, the chest deflating and then we will notice the sensation the airflow causes at our nose. Again there is a gap between ex- and inhalation and then the next inhalation will begin and so on and so on. If you are not familiar with abdominal breathing or your belly will not move at all, be aware of the movement of your chest instead. This technique is called ‘following’ the breath.

We want to be aware of the sensations the breath causes along its way in our body. At first we let the breathing go comfortably and naturally without influencing it. When we inhale the air enters the nose. We can be aware of this at some point at the inner skin of the nose, the nostrils or the upper lip. If you have difficulties to find the point of touch, you may breathe forcefully for a couple of breaths. Then the air travels along the upper palate and the throat into our lungs (which is difficult to be aware of) and we will notice that our chest widens and the belly rises. Then there is a gap between in- and exhalation and when we start exhaling, we are aware of the abdomen sinking back, the chest deflating and then we will notice the sensation the airflow causes at our nose. Again there is a gap between ex- and inhalation and then the next inhalation will begin and so on and so on. If you are not familiar with abdominal breathing or your belly will not move at all, be aware of the movement of your chest instead. This technique is called ‘following’ the breath. Why are we looking for impermanence, and where exactly should we look for it? We are looking for impermanence to allow the mind to let go of all the things it is chasing after because this constantly chasing after things, clinging to them, is what causes our problems. Intellectually this concept of impermanence isn’t difficult to understand, we know it already, but the mind is unable to take the necessary steps out of misery unless it really has experienced impermanence.

Why are we looking for impermanence, and where exactly should we look for it? We are looking for impermanence to allow the mind to let go of all the things it is chasing after because this constantly chasing after things, clinging to them, is what causes our problems. Intellectually this concept of impermanence isn’t difficult to understand, we know it already, but the mind is unable to take the necessary steps out of misery unless it really has experienced impermanence. The purpose of doing loving kindness meditation is to develop friendliness and wishes of wellbeing towards all sentient beings, including yourself. It is the method of choice to lessen animosity and anger; the sense of self, selfishness will decrease. It promotes tolerance, patience, gratitude and a forgiving heart. Usually it is practised together with developing compassion and sympathetic joy. Loving kindness meditation has nothing to do with that sentimental “I love you all and everybody is just wonderful”, but it sees very clearly the positive and negative aspects of oneself and others. It brings about positive attitudinal changes as it systematically develops the quality of loving acceptance.

The purpose of doing loving kindness meditation is to develop friendliness and wishes of wellbeing towards all sentient beings, including yourself. It is the method of choice to lessen animosity and anger; the sense of self, selfishness will decrease. It promotes tolerance, patience, gratitude and a forgiving heart. Usually it is practised together with developing compassion and sympathetic joy. Loving kindness meditation has nothing to do with that sentimental “I love you all and everybody is just wonderful”, but it sees very clearly the positive and negative aspects of oneself and others. It brings about positive attitudinal changes as it systematically develops the quality of loving acceptance.